Kurdish Identity and Diaspora Belonging: Balancing Multiple Identities

Introduction

This brief study delves into the intricate ways layered identities co-exist and evolve within the Kurdish diaspora, shaped by a complex interplay of internal and external forces—such as language, family ties, community bonds, and the cultural dynamics of the host country. By highlighting the factors that diasporic Kurds identify as contributing to the success or challenges of balancing their heritage with the identity of their adopted home, this research sheds light on the key elements that shape and preserve Kurdish identity abroad.

Literature Review

Identity may not have a universal definition, it is widely considered however as the collection of characteristics, beliefs, values, and experiences that make up who a person is and how they see themselves. A key concept taken from Stuart Hall’s essay "Cultural Identity and Diaspora" is that identity is not fixed but rather an ongoing process shaped by historical and cultural contexts including personal and collective experiences (Hall, 2014). Identity encompasses various aspects such as ethnicity, nationality, language, religion, and personal values for those in the diaspora, and as individuals mature both mentally and physically, these aspects may evolve, causing one’s identity to also shift over time. This evolution can lead to either greater harmony or increased tension in the coexistence of multiple identities. Renowned linguist Noam Chomsky recognizes that language is often the most immediate foundation in the structure of one’s identity and cognitive structure (Chomsky,1984). Language is therefore a powerful marker of identity construction for individuals of shared ethnicity and serves as a means of expressing one’s culture through communication. Benedict Anderson argues that a nation is moreover imagined as a community, a deep and horizontal fraternity that united all of its members across age, class, color, creed, gender – irrespective of actually existing divisions (Anderson, 2016). The common thread that binds ethnic groups living in diaspora apart from language is also the shared vision of a homeland - a nation. Jowan Mahmod presents the argument that diaspora Kurds have conflicting views and emotions among young diasporic Kurds, and their changed views that challenge the Kurdish perceptions of identity as a static and unified entity. Kurds are constantly reminded that their homeland is not a recognized nation, which can be seen as fueling a stronger desire to preserve their cultural identity. Mahmod also argues that diasporic populations often have tragic stories of violence in the homeland and individual experiences of genocide (Mahmod, 2019). Individual experiences, whether Kurds recall them firsthand or were exposed to their families' trauma through oral stories shared by parents or elders or through social media, news outlets, films, play a key role in shaping identity as the identity of Kurds in diaspora continues to evolve. While the process of balancing multiple identities varies from person to person, it is significant to understand these experiences to fully grasp Kurdish identity and the sense of belonging in the diaspora.

Theoretical Framework

Identity as a concept is defined as the set of qualities, beliefs, personality traits, appearance, and/or expressions that characterize a person or a group (Jary & Jary, 2000). The etymology of the term "identity" is from the Latin noun identitas, and means an individual's mental image of themselves and their "sameness with others.”

Cultural identity is defined as a collective and shared sense of self, rooted in common historical experiences, memories, and cultural practices. It emphasizes the sense of belonging to a unified cultural group, which gives individuals a stable sense of who they are through collective memory of their history, language, and struggles, which unites them as a group (Hall, 2014). Hall stresses that identity construction is never fixed; it evolves through time, interaction, social and political relationships, and experiences (2014).

Diaspora refers to the dispersion of people from their homeland; as a dispersed population that shares a common origin or homeland but lives outside of it, often due to historical forces like migration, displacement, or exile (Cohen,1997).

Belonging is a multi-layered concept that goes beyond mere membership in a community or society. Yuval-Davis (2011) emphasizes that belonging is not just about social location but also involves emotional attachment and a sense of being at home in a specific context. Her definition of belonging incorporates social, political, and personal dimensions, which can change over time and in different spaces (2011). In the context of this study, diaspora belonging refers to feeling a sense of acceptance and attachment, as well as an ability to conform to the social norms and etiquette of one’s country of residence.

Research Methodology

This study utilized two methods for data collection: an online survey with 46 participants and interviews with 10 individuals who were either born in or relocated to their host countries between the ages of 2 and 9. Quantitative research methods were used in this study to analyze the data collected from the survey and compile into statistical representations and pie charts. Additionally, qualitative research methods were used to illuminate the participants' experiences and the meanings they attach to the construction and perceptions of their multiple identities.

The Results of Online Survey

The online survey had 46 participants; 53% of which were female while 47% of which were male.

The majority of the participant’s ages ranged between 21-37 years.

The majority of the participants reside in Canada, America, the UK, and Norway.

All participants of this study identified as Kurdish, however expressed that they were Kurdish from various countries - Iraq, Iran, Syria, and Turkey.

The majority of which were from Iraqi Kurdistan, and were of Behdin (Kurmanji) and Sorani dialect speakers.

Survey Questions

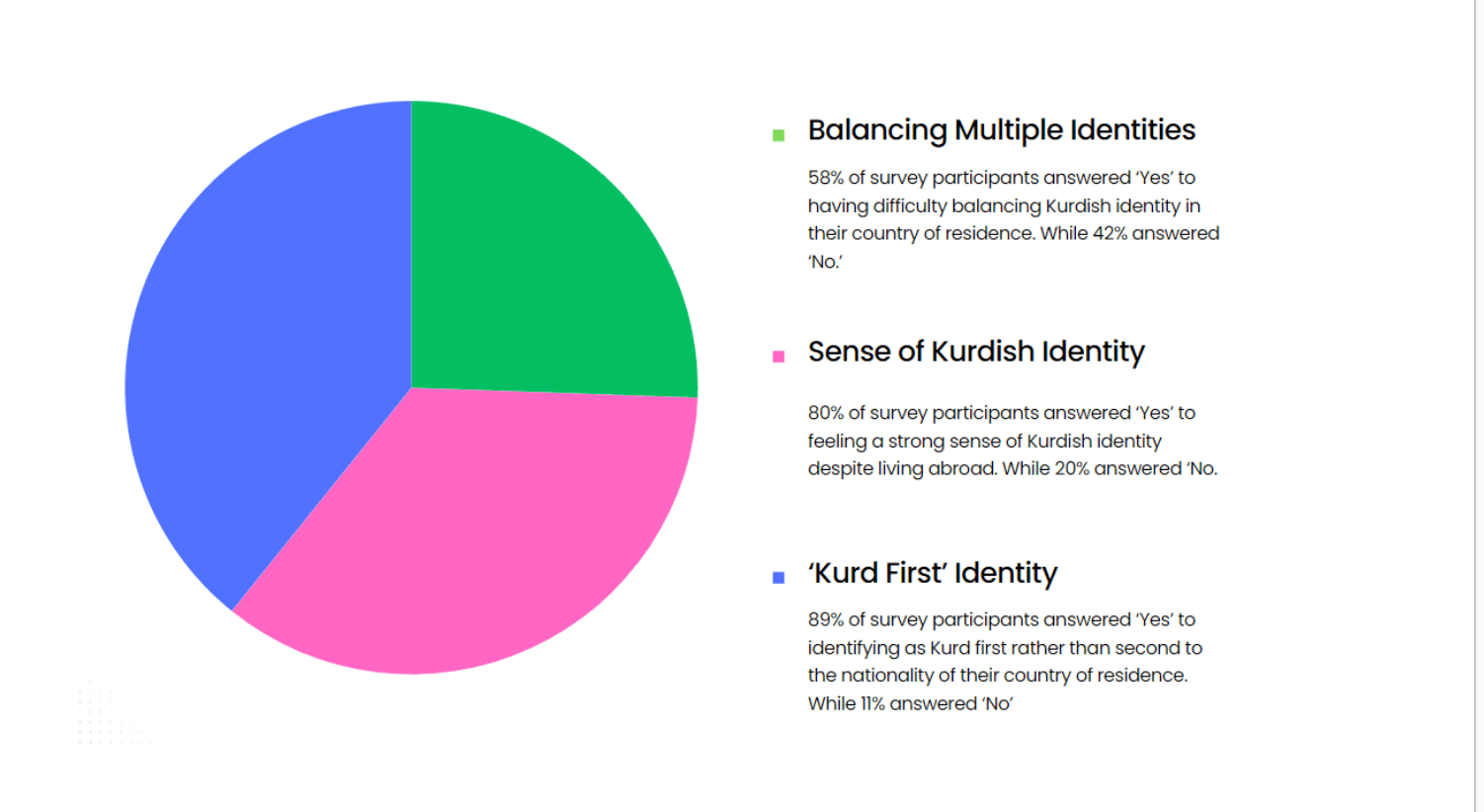

1. Do you have difficulty balancing your Kurdish identity in your resident country?

2. Do you feel a strong sense of Kurdish identity despite living abroad?

3. Do you identify as a Kurd first, or second to the nationality of your country of residence?

Main Findings

58% of survey participants answered ‘Yes’ to having difficulty balancing Kurdish identity in their country of residence. While 42% answered ‘No.’

80% of survey participants answered ‘Yes’ to feeling a strong sense of Kurdish identity despite living abroad. While 20% answered ‘No.’

89% of survey participants answered ‘Yes’ to identifying as Kurd first rather than second to the nationality of their country of residence. While 11% answered ‘No’

Interview Results

The 10 interview participants were asked four questions:

Question 1: How would you describe your sense of Kurdish identity while living in the diaspora?

Question 2: In what ways do you feel connected to your Kurdish heritage while living abroad? Are there moments when you feel distant from it?

Question 3: Do you feel more connected to the Kurdish community, your host country's culture, or both? How do you navigate these different identities?

Question 4: What factors were most influential in preserving your Kurdish identity?

The majority of interview participants, 80%, described their Kurdish identity as integral to "who they are"—deeply instilled in their sense of self and a defining aspect of their overall identity. 100% of interview participants indicated that their Kurdish identity was strongly shaped by speaking Kurdish and engaging in traditions preserved by their community and elders, as well as past traumas of their families as a result of persecution, genocide, and fleeing war. Additionally, 90% of participants live in communities with a significant Kurdish population that maintain traditions such as family visitations, weddings, funeral practices, Eid customs, and more. This connection to their community allowed them to feel "connected" to their Kurdish heritage. Furthermore, 92% of participants emphasized their parents' strong desire to preserve cultural traditions as a way to instill a deep sense of Kurdish identity in their children, reminding them that they are "different" from the identity of their host country—religiously, culturally, morally, and ethnically. However, 65% of participants noted that they felt distanced from their Kurdish heritage when interacting with non-Kurdish individuals in their host countries, while 35% stated they never felt distant from their Kurdish culture. All participants, 100%, expressed that language is the most important factor in shaping and preserving their Kurdish identity. Moreover, 85% of interviewees agreed that identity is fluid and can evolve over time due to life experiences, relationships, and societal influences. Nonetheless, every participant emphasized the significant role that their Kurdish heritage played in shaping both their past and current identities. In terms of balance, 75% of participants reported that their Kurdish identity was difficult to reconcile with their host country’s culture during their younger years, particularly in elementary and high school, when they struggled to articulate aspects of their culture to non-Kurds. Additionally, 71% of participants stated that they navigate their layered identities by connecting socially with fellow Kurds and attending Kurdish events. Meanwhile, 22% reported embracing the cultural identity of their host country, and 11% of participants stated they did not experience any significant difficulties in balancing their Kurdish and host-country identities.

Discussion

While each Kurdish individual's experience in the diaspora is shaped by their unique upbringing and community, the research collected from participants in this study reveals a common thread in the construction of Kurdish identity. For the majority of participants in this study, this thread is intricately woven through the upholding of Kurdish traditions, language, and a strong sense of community; for others, their Kurdish identity serves as a simple reminder and renders little significance in the way one identifies his/her sense of self. This corroborates Anderson’s (2016) unification through imagined community theory, as many diasporic Kurds hold a shared connection as part of a larger collective. Also, Hall’s (2014) argument that identity is a shape-shifting and enduring process is underscored in this brief study. This study also highlights the significance of language as a foundational pillar in preserving Kurdish identity. Chomsky's (1984) assertion that language forms the strongest basis for both identity and cognitive development reinforces this idea, emphasizing the central role language plays in shaping one's sense of self. Nevertheless, participants in both surveys and interviews expressed a shared sentiment of feeling connected to both their host country's identity and their Kurdish identity, with the emphasis on one or the other varying depending on context—such as at school, non-Kurdish social events, or in the workplace. Multiple identities evolve and reconcile themselves through maturity, experiences, and introspection of themselves and the perception of the world around them. Kurds in the diaspora often face the challenge of reconciling multiple identities as they adapt to the culture of their host country while raising families and passing Kurdish traditions onto their children. This sense of "us" and "them," which participants emphasized their parents aimed to instill, is not viewed as a hostile juxtaposition but rather as an added dimensionality and vibrant layer to the self-identity of diasporic Kurds. The findings of this study suggest that multiple identities coexist more harmoniously as individuals mature, becoming more introspective, articulate, and comfortable in expressing their multiple identities.

Conclusion

The research reveals a dynamic interplay of factors that both strengthen and challenge the balancing of layered identities—specifically, the Kurdish identity and that of the host country. Elements such as language, cultural traditions, and the collective memory of trauma from displacement and conflict emerge as pivotal in shaping Kurdish identity abroad. Yet, this process is anything but uniform. Individual experiences, generational shifts, and varying levels of integration into host societies all influence how Kurds construct and express their identities in the diaspora. While many Kurds in the diaspora develop a sense of belonging and attachment to their adopted countries, the findings suggest that Kurdish identity remains a deeply ingrained aspect of their self-concept, woven alongside their connection to their adopted homeland.

References

[1] Albury, N. J., & Schluter, A. A. (2021). Introduction: Reimagining language and belonging in the diaspora. Lingua, 263, Article 103157. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2021.103157

[2] Anderson, Benedict. 2016. Imagined Communities. London, England: Verso Books.

[3] Barbosa, Eduardo. (2023). The Relationship Between Language and Identity.

The Relationship Between Language and Identity | by CLAC VIII - 2023.1 | Medium

[4] Canagarajah, S., & Silberstein, S. (2012). Diaspora Identities and Language. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 11(2), 81–84. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2012.667296

[5] Cohen, R. (1997). Global Diasporas: An Introduction. United Kingdom: UCL Press

[6] García, O., Flores, N., & Spotti, M. (2017). The Oxford Handbook of Language and Society. Oxford, United Kingdom: Oxford University Press.

[7] Hall, Stuart.(2014). “Cultural Identity and Diaspora.” Undoing Place? 222-237. hallculturalidentityanddiaspora.pdf (warwick.ac.uk)

[8] Jary, D., & Jary, J. (2000). Collins Dictionary of Sociology. United Kingdom: Harper Collins. https://books.google.no/books?id=vavLSAAACAAJ

[9] Mahmod, Jowan. “New Online Communities and New Identity Making: The Curious Case of the Kurdish Diaspora.” Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Studies 6, no. 2 (2019) 34–43. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48710218.

[10] Online Etymology Dictionary. Retrieved from: identity | Etymology of identity by etymonline

[11] Osiatyński, Wiktor. (1984). Contrasts: Soviet and American Thinkers Discuss the Future. Pp. 95-101. The University of California: MacMillan Press. On Language and Culture, Noam Chomsky interviewed by Wiktor Osiatynski

[12] Yuval-Davis, Nira (2011). The Politics of Belonging: Intersectional Contestations. United Kingdom: SAGE Publications.